Welcome to my second batch of articles for February which include:

· St Valentine

· a look at chard plus a recipe

· some more jobs to be getting on with in February

· my just-for-fun Wordsearch

· latest news

St Valentine

Yesterday was St Valentine’s Day, the patron saint of love, affianced couples, and happy marriages. (Although how he actually ended up as such is shrouded in mystery and sometimes disputed. Be that as it may, I’m not going to be a party pooper so let’s just go along with it.)

He’s also one of the saints associated with announcing the arrival of Spring, taking an especial interest in plant growth and the flowers that follow.

No wonder then that flowers figure heavily when lovers celebrate his day.

Red roses spring immediately to mind, which isn’t surprising since they have been a symbol of love for a very long time.

During the Victorian era, floriography – otherwise known as the language of flowers, where each flower carries with it a particular meaning, and sometimes more than one – became popular. As well as being a beautiful gift, the sending of a posy of flowers took on an additional function – it could also convey a message. For example, with Valentine’s Day in mind, I had a look in a book called simply The Language of Flowers1 and discovered that: fennel = worthy of all praise, honeysuckle = bonds of love, mint = virtue, myrtle = love, red rosebuds = purity and loveliness, red tulips = declaration of love, the rose ‘Gloire de Dijon’ = a messenger of love, single pinks = pure love.

So, disregarding any seasonality of the flowers, if you got a bouquet with that lot in, you know your admirer is head over heels for you!

Another flower that speaks of love is the orchid. It’s long been a symbol of romance: indeed, the genus Paphiopedilum derives its name from the Temple at Paphos which was dedicated to Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love. Its common name of Venus slipper orchid is also apt since Venus is the Roman equivalent of Aphrodite.

And, along with a host of other Saints – including Ambrose, Bernard of Clairvaux, and Gognait – Valentine is also a patron saint of bees and beekeepers: I had to get a reference to bees in somewhere in this article! One of his tasks is to look out for the health of bees (no mean feat) and to ensure the sweetness of honey. Which takes us nicely back to flowers because honey is made from the nectar of flowers, of course.

So I reckon we should raise our hats this Valentine-tide to the patron saint of love, spring, and bees.

1 Pickston, M, (1968) The Language of Flowers, Michael Joseph Ltd. London.

Let’s turn our attention to a vegetable now.

Chard

I first came across the name Chard when I was told as a youngster that my best friend’s Grandad’s second name was Chard. Somewhat unusual, but it seems that there was a tradition in their family of naming the children after the location where they were born – in this case Chard, in Somerset. (Good job he wasn’t born in Ugley.) This gobbet of information somehow stuck in my brain and gave rise to much bafflement when, much later, I later discovered chard, the vegetable. Why on earth would it be named after a town in Somerset? Well, it’s not, of course.

Apparently, the edible stalks of cardoons (the thistly artichoke-type vegetable) were called ‘chards’, which can be traced to the Latin and French for thistle, so, since the stems of our vegetable resemble said stalks the name was transferred, and there we have it.

So far, so good, but what about the Swiss bit? For that there doesn’t seem to be any sort of definitive explanation. The prefix appears to have been added during the 19th century, probably by the publishers of some seed catalogues, to distinguish ‘our’ chard from French spinach varieties, but even that is open to debate. I have a feeling that it’s just about as authentically Swiss as Swiss roll!

I can’t help but think that poor old chard might have something of an identity crisis since it’s also known as perpetual spinach, spinach beet, silverbeet, leafbeet and rainbow beet! What is certain, however, is that it is definitely not spinach, which constitutes a different genus entirely.

Whatever the origins of its name, and whatever it’s been called over the years, chard has undoubtedly been grown in China since the 7th century and it seems highly likely that it was part of the horticultural output of the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East some centuries before that. In sixteenth century England, John Gerard wrote of a beet with red stalks, the seeds of which had been brought to him ‘from beyond the seas’ in 1596. The progeny of his red-stemmed beet were ‘plants of many and variable colours’ – the forerunner of our ‘Bright Lights’ strain of chard, no doubt. He wasn’t wrong in calling chard a beet, though, since it is a member of the beet family, its Latin name being Beta vulgaris subsp. cicla.

From an aesthetic point of view, simply calling chard a vegetable doesn’t really do it justice. A happy chard plant has leaves that gleam and shine like patent leather, catching the light and reflecting it with the intensity of an emerald. The ‘original’ Swiss chard has white stems but as Gerard found out, you can also get varieties with coloured stems, ranging from the deepest burgundy red to the palest honey yellow – all of which look great in the veg patch. They look good in the ornamental flower border, too, adding a texture and colour all of their own.

Growing chard

You can sow the knobbly seeds of chard directly into rich, moisture-retentive soil in drills about 2.5 cm deep and spaced about 10cm apart. Rows should be about 40cm apart. When the seedlings are big enough, thin them out so you have one good plant every 30cm or so. You can begin sowing outdoors in April when the soil has warmed up a bit. In order to be able to enjoy a succession of delicious young leaves, you could sow more seeds every three weeks. Sow your final batch in early August for harvesting during the winter months and into early spring.

You can also sow the seed into individual modules indoors, planting your little plug plants out when the roots have developed to a sufficient degree, and they have established some sturdy top growth. Give them the same spacing as for thinned-out, outdoor-sown plants.

Chard needs little care other than being kept weed-free and watered if necessary. Keeping them too dry in the first season will stress them and they will bolt or run to seed. Because chard is a biennial, it will do this in the second year anyway, but you don’t want to cause this to happen too early. If a flowering stem does appear, however, simply cut it out as soon as you notice it, give the plant a good soak and in no time at all you will notice that new leaves will appear.

It is also as well to remove any outer leaves that are not up to scratch before they start to deteriorate and rot otherwise disease might set in. Consign any unwanted leaves to the compost bin.

Chard is a pretty tough customer. With temperatures often sinking below zero during the winter months, you would expect it to be reduced to a soggy mess, beyond redemption, but no – it’s surprisingly resilient. Wait until the frost has disappeared and the leaves will perk up again. If, however, you want to have some fresh leaves throughout winter, cover the plants with some horticultural fleece or cloches at the beginning of winter; this little bit of extra care will see them safely through the cold season.

Harvesting chard

As soon as it is big enough you can cut the whole plant, as you would a head of celery, leaving the root to throw up new leaves. I find the ‘cut and come again’ method suits us best, however. This is where you cut the outside leaves as soon as they are big enough, leaving the centre of the plant intact so it can carry on growing.

Cooking chard

Even though the stem colour varies so much they tend to end up tasting more or less the same after being cooked. I always strip the leafy bit from the stem and cook them separately – the stems need a little longer cooking time, but not much, so don’t boil them to death like my Gran used to do with the Christmas Brussels sprouts.

Here’s a good wheeze for when April 1st comes round - I fooled my husband with a chard crumble: if you slice and season the stalks, top them with a herb and cheese crumble, bake it and serve it with a cheese sauce, it looks remarkably similar to rhubarb crumble and custard! I owned up, of course, but his face after the first mouthful was a real picture!

Both leaf and stems are great in a stir-fry, and I like to use very young leaves in a salad. They can be a little on the bitter side, but certainly no more, say, than rocket. I actually quite like the slight zing that stimulates your taste buds and wakes up the appetite.

Chard is also very good for you. It’s jam packed with Vitamins (especially A, K and C), phytonutrients, has antioxidant properties, and is said to contribute to blood sugar regulation – so there is really no excuse for not giving this delicious veg a go – and a grow!

Time for my …

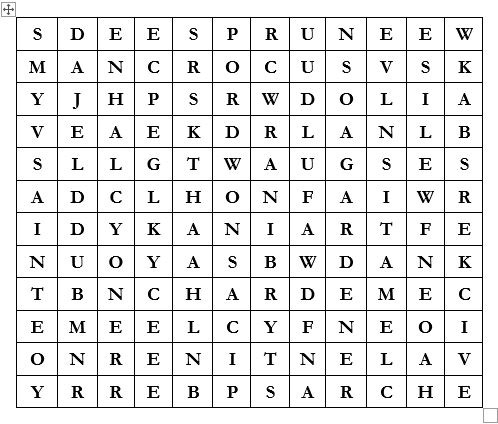

Just for Fun Wordsearch!

All the words come from my February articles – can you find them in the grid?

The words can be vertical, horizontal, or diagonal – and in any direction.

ANNUALS BEE BUDDLEJA CHARD CLEMATIS CROCUS GARDENER HALCYON KINGFISHER LOVE PRUNE RASPBERRY ROSE SAINT SALLEY SEEDS SNOWDROP SOW VALENTINE VICKERS

Here are some more …

Jobs for February

Late-flowering clematis (Group 3, such as Viticella) can be pruned back now. Cut to just above a pair of healthy buds, about 30cm from the base.

Deciduous grasses, such as Molinia and Miscanthus, can be given a haircut before new growth start to emerge.

Keep an eye out for wildlife: continue to feed the birds and be extra vigilant if you are tending your compost heap – hedgehogs and grass snakes may be hibernating.

Start sowing hardy annuals under cover (see my article of 1st February about sowing seeds.)

At the end of February you can also start chitting seed potatoes. Place them in egg trays and keep them in a light, cool, frost-free place to get them going.

If your winter containers are looking a bit forlorn, refresh them with some potted primroses or early flowering bulbs that can be found at garden centres or nurseries.

News

Good news! The Government has rejected an emergency application of Cruiser SB, a neonicotinoid, to be used on sugar beet to counter virus yellows which is transmitted by aphids.

Defra has been quoted as saying that there was 'clear and abundant evidence' that the neonicotinoid was 'extremely toxic' to pollinators such as bees.

The previous Conservative Government granted its use for five consecutive years, but the new Labour Government is advocating industry-led developments to prevent virus yellows infection rather than using neonics.

Government Minister Emma Hardy has said: “The UK Government is setting out its plans to deliver its commitment to end the use in England of toxic neonicotinoid pesticides that threaten vital pollinators. […] Emergency authorisations are temporary measures intended to protect crops in exceptional circumstances. We do not consider that they should be used to perpetuate the use of neonicotinoids that can have a long-term effect on biodiversity.” (See https://tinyurl.com/ys7e8rbc)

In the Policy paper A new approach to the use of certain neonicotinoids on crops grown in England the Government has said: “We are committed to working with stakeholders to support the growers to succeed without neonicotinoids. […] The government is also committed to developing and supporting the adoption of measures, such as integrated pest management, that can help farmers and others move away from reliance on pesticides in general and specific products.” (See https://tinyurl.com/2rp3r3ba)

Picture credits:

Rose, Orchid, Primrose: Pixabay. All others: my own

For more information about The Bee Garden and what I get up to, please have a look at my website www.thebeegarden.co.uk which also features my online shop.

And as a thankyou for signing up to receive these articles you can get a 10% discount on all items in the shop: simply enter SUB10 at the checkout and the discount is automatically activated.